Drones for Science

Written by Oliver Halsey & Meg Schmitt

October 2016

Drones have been causing a stir in the past few years. Love them or hate them, drones have opened up a whole new set of opportunities for a variety of fields and industries.

While their original intent, and now renowned primary association, was for espionage and war-making at a distance, drones have been put to many uses since their entry onto the broader consumer market. Besides becoming a tech-toy for people of all ages and a possibly game-changing commercial delivery technology, drones have lent important new tools to filmmakers and photographers, by allowing the capture of aerial footage previously unobtainable without access to plane or helicopter.

Photographers and other visual artists aren’t the only ones sending drones skyward. Scientists and researchers are putting drones to use investigating some of the toughest questions. From distance monitoring to visual mapping, drones are proving extremely applicable to many fields of research, capturing vast amounts of data with relative ease.

Recently, authorities have begun clamping down on the flying of drones due to the reckless piloting of a few. Many find drones objectionable not just for their purported invasion of individual and corporate privacy. Drone misuse has been earning headlines for reasons such as crashing into planes at busy airports, causing human injury, as well as being responsible for damage to wildlife and national parks.

In many countries authorities are requiring licences to fly drones for any purpose, and here in Namibia, guards of the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) have been told to shoot down drones on sight for those without the correct permits. Poachers have been found using drones as a way to scan for ivory from the sky, and as rhino populations are under severe threat, as well as neighbouring South Africa’s elephant poaching problems that continue to grow, authorities must resort to these measures.

Willem Kubeb, an MET guard at Etosha National Park for over 20 years, is familiar with the poaching of rhinos and elephants for their ivory.

Recently a team from The Auckland University of Technology (AUT), New Zealand travelled to Gobabeb Research and Training Centre, a desert research station in Namibia, to fly their drones where little over-land surveying has been done. AUT have mapped areas in various continents including Antarctica to measure the abundance of certain organisms.

The arid, otherworldly landscapes of the Namib Desert pose significant scientific interest.

I joined the AUT drone team where we travelled to “Welwitschia Wash”, an area located in the Namib Desert, on the edge of the Sand Sea and home to a sizeable population of the fascinating and ancient plant, Welwitschia mirabilis. The Welwitschia plants at the wash have been monitored in a range of long-term research projects by Gobabeb for nearly 40 years and are a continual source of new research in Namibia.

The objective of the team was to capture a series of still photographs high above the wash and then stitch them together using image processing software, resulting in an interactive and accurate three-dimensional map of the region that captures the topography and groundcover.

Dr Barbara Bollard-Breen and Dr Ashray Doshi from AUT prepare their drone for take off in the Namib Desert.

The 3D maps can be used as an important source of primary information gathering on large spatial scales, making it particularly useful for vast landscapes. These maps are useful educational tools that allow anyone to gain access to the details of these remote areas of our planet. AUT are optimistic for the future of drone use in science and believe that their methods have the potential to obtain accurate information of an area, providing insight into species diversity and population as well as geological changes that manifested over millennia.

Drone pilot and robotics engineer, Dr Ashray Doshi flies over Welwitschia Wash.

The AUT drone team were keen to point out another distinct advantage of using drones in areas such as Welwitschia Wash – minimizing the impact of human activity. There are little to no terrestrial places remaining on our planet left untouched by humans, and gaining access to pristine areas and unique ecosystems, even for scientific purposes can be considered difficult, dangerous or unethical. The use of drones and rovers has the potential to bypass these issues.

Dr Cornelis van der Waal, associate of Gobabeb, is using drones to map a number of locations across Namibia to survey woody and herbaceous trees, primarily for livestock management in savannah communities. Dr van der Waal wants to see whether such areas are suitable for browsers or grazers. This analysis provides a link to satellite data through remote sensing, validating the satellite’s results by “ground-truthing”.

When considering the often large expanses of livestock-inhabited savannah in Namibia, drones were an obvious source of help for his project. “[Drones] allow you to cover a large area in a short amount of time. Mapping an area from the ground could take days compared to what a drone can achieve in a matter of minutes.” Dr van der Waal says.

Chris Woodington and Dr Cornelis van der Waal of Gobabeb Research and Training Centre prepare a drone for flight.

Much like the AUT team, Dr van der Waal uses the drone to perform aerial surveys consisting of consecutive transect lines. The drone’s camera takes a series of continuous, still photographs from the air which Dr van der Wall then stitches together using image processing software to form a 3D map. Analysing the resulting map can determine species composition and diversity within the area.

The creation of a map is a process where hundreds of photographs must be combined. Trees from a bird’s eye (or drone’s eye) view can be seen on the screen on the left.

Having a well-equipped drone is essential for using the tool to its full potential. Besides the equipment on the drone itself, finding the best conditions under which to fly is important. The weather has a great impact on drones’ applications - drones do not perform to their best ability under windy conditions, as fighting against the wind is a major drain on often-limited battery power. The position of the sun can also be a factor to consider, because if it is low in the sky unwanted shadows are cast over survey images, obscuring patches of the landscape.

Drones have also been put to use in the vicinity of Gobabeb. Jasper Vanneuville, a student from Vives University College in Belgium has been measuring the growth of Faidherbia albida and Vachellia erioloba trees over time. The trees are concentrated in and along the Kuiseb River, an ephemeral river that runs through the central Namib where the sandy soils have enough water retention to maintain a lush ‘linear oasis’ at the foot of the Namib Sand Sea’s dunes.

A drone is ready for take-off at Gobabeb Research and Training Centre in the Namib Desert.

Vanneuville is studying the area’s trees to monitor the difference in growth (height, girth and canopy) from when the trees were last measured several decades ago. Some of the trees have grown significantly and this can be attributed to the flooding of the ephemeral river several years ago.

Jasper Vanneuville of Vives University College, Belgium measures trees from the ground in the ephemeral Kuiseb River.

The Namib Desert is an incredibly arid environment where rainfall is less than 30 mm per year on average. What rainfall does fall is inconsistent, ranging from zero to nearly 120 mm annually, preventing even these hardy acacia tree species from settling out on the open plains. The Kuiseb River is invaluable as a source of water, and thus life due to the shade and fodder producing trees it supports. Although it is ephemeral, and flows infrequently, the Kuiseb aquifer beneath the riverbed sustains the plant life and dependent animals even in dry years. The Kuiseb’s riverbed covers only 1% of the surface area of Namib-Naukluft Park, but supports more than 50% of the biomass in the NNP.

A dead tree stands in the sand against a background of green life on the banks of the Kuiseb.

Despite flooding events sometimes being years apart, the floodwater seeps into the sandy soil and is retained deep under the surface. Trees and plants can absorb this reserve when needed, their roots extending many metres underground to quench their thirst. When the Kuiseb does flow, it flows with rain falling inland, over the Khomas Hochland region nearly 200 km away. This is what floods the river along the Namib Sand Sea, not the rare local rainfall.

The Kuiseb River, which runs through the central Namib Desert, boarding the Namib Sand Sea, runs dry for years at a time.

Observing these resilient trees and their growth patterns can improve our understanding of the role flooding has in this riverine ecosystem. Much of Vanneuville’s measurements were first done on foot – ‘hugging’ the trees to obtain tree-diameter (diameter at breast height, or DBH), and using a clinometer to get tree height. Both of these techniques are tried and field-trusted measurements in ecology – but they face novel complications in this environment. With flood flows continually changing the topography of the riverbed, it can be surprisingly tricky to get an accurate reading of tree height – a tree might have effectively ‘sank’ with the moving of the river’s banks, or ‘grown’ from sand being swept aside.

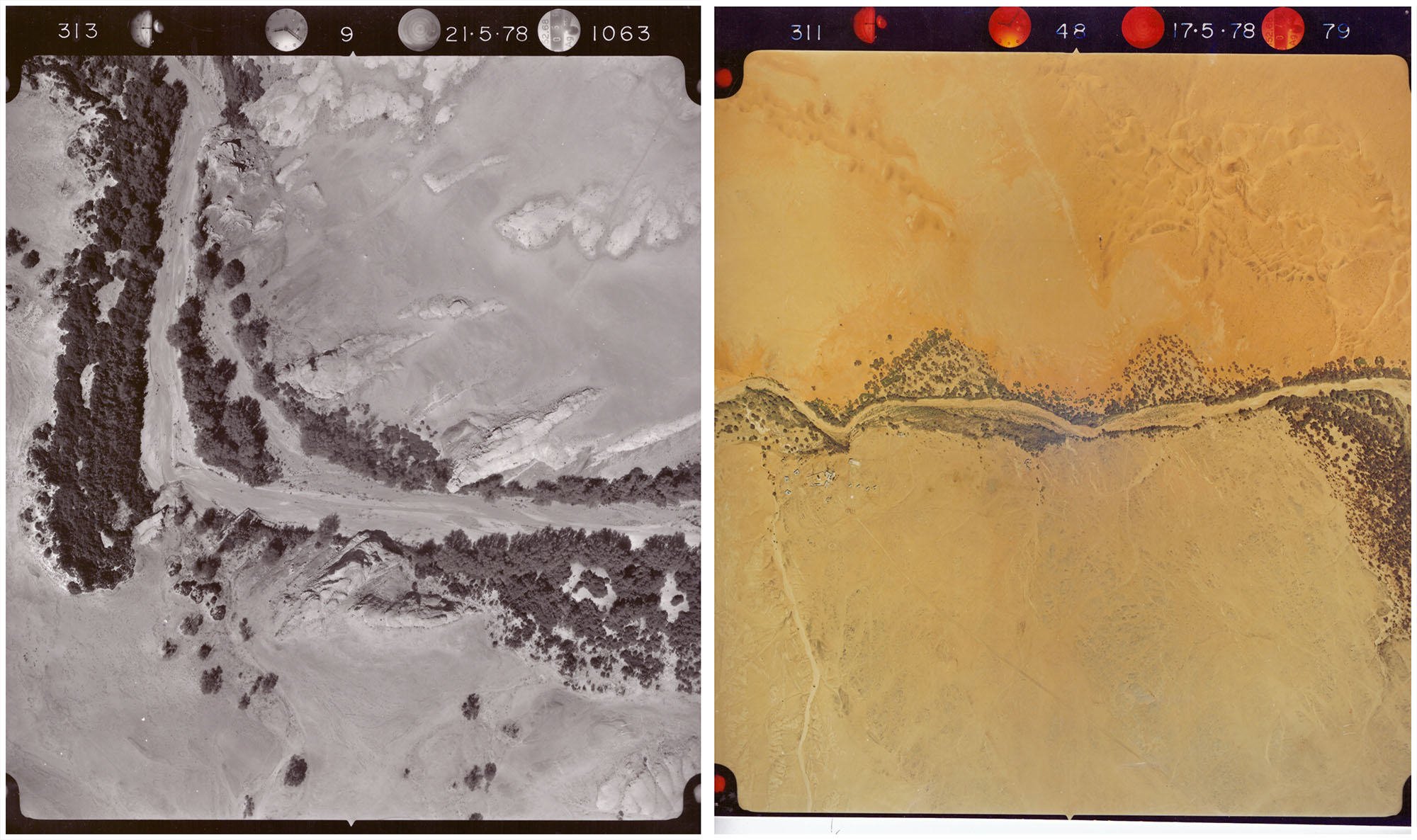

While getting accurate measurements for trees’ trunks is not easy, drone technology has made obtaining accurate canopy measurements a breeze. Using the drone’s camera, Vanneuville can see the tree canopy cover over his study area and compare this with photographs of the area taken decades ago. The previous photographs taken in the 1970’s took a lot more money, time and resources to obtain. Today, researchers can take detailed photos of an area, scale them to size, and derive direct comparison of decades of growth in only a few hours’ work.

Images taken in 1978 capture the area in detail, however they were vastly more expensive and time consuming to create. Modern digital cameras on drones are able to capture a location in even more detail than satellite imagery of the past century. Photo credit: Gobabeb Research and Training Centre.

With the wide availability of drones and the continual expansion of the technology, poachers can and are using them to scout and track rhinos and elephants for longer periods of time. However, the progression of technology must be embraced, and whilst strict supervision or permits may seem like drudgery, the misuse of drones can have disastrous consequences for our planet’s wildlife.

Despite some negative press surrounding drones, when used considerately, the technology undoubtedly has the potential to broaden our understanding of the world whilst reducing human impact on the environment. The work of researchers like Vanneuville, van der Waal, and the AUT drone team is revealing the many uses drones can be put to. The effective use of drones has the potential to further scientific research goals and improve research methodology.

More information about the The Auckland University of Technology AUT drone team can be found at their website, ‘unmanned science’: http://unmanned.co.nz/

All images unless stated otherwise are copyright © Oliver Halsey.